The concept of beauty and what makes something beautiful has been discussed since the dawn of philosophy, and will likely be the topic of many discussions for thousands of years to come. What is beauty? What is it that makes something beautiful?

There have been various approaches to answering this question, some are scientific in nature, some are rooted in philosophy and some in religion. Beauty is something that we all understand and experience, but it is something that none of us can really explain. Perhaps the great German Renaissance artist, Albrecht Dürer, stated it best when he said:

“What beauty is, I know not, though it dependeth upon many things…”

While we may not all be able to agree on what is beautiful and what is not, we all can agree that there are certain things which seem to have qualities which can touch us deeply. Understanding these qualities – whether they come from within us, or from within the objects we create–can be powerful tools to enrich our lives and the lives of others.

Defining Beauty

We use the word “beauty” without thinking about what it really means. We use the word almost instinctively to describe qualities of objects, of people, of situations. Typically there is little need to justify the choice of the word, as it is one that we all can seem to agree on in one way or another.

We also have little problem accepting that others can find beauty in things that we cannot. We might be bewildered at the types of objects and things that some people consider to be beautiful, but we also have grown to appreciate that “beauty, at times, must be in the eye of the beholder.” There could be something about the object that they perceive that we don’t, or it could be that they’ve had experiences in their life which make them able to recognize the beauty within an object which we cannot. Perhaps, there is nothing in the object which is beautiful at all, and beauty is nothing more than a neurological experience which takes place only inside of our heads.

Beauty as a Neurological Experience

One way of looking at beauty is the idea that we perceive something as beautiful because it triggers some sort of physical response within us which is agreeable. This response to stimuli can be potent.

We cannot always explain it merely due to the complexity of our physical bodies and systems, but this might seem like a very logical explanation. I can certainly imagine that a work of art might somehow help me recall a positive childhood experience: the colors were just the same, or an object in the room or picture reminded me of something else from my past conditioning.

In 1998 V.S. Ramachandran and William Hirstein published a report called “The Science of Art, A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience.” This was the first study of its kind to investigate how the human brain responded to art. In the study, they suggested that artists consciously or subconsciously used specific visual design principles to stimulate the visual areas of the brain to evoke a direct emotional response. If certain principles of art were defined and employed, the brain would respond to those in a specific way.

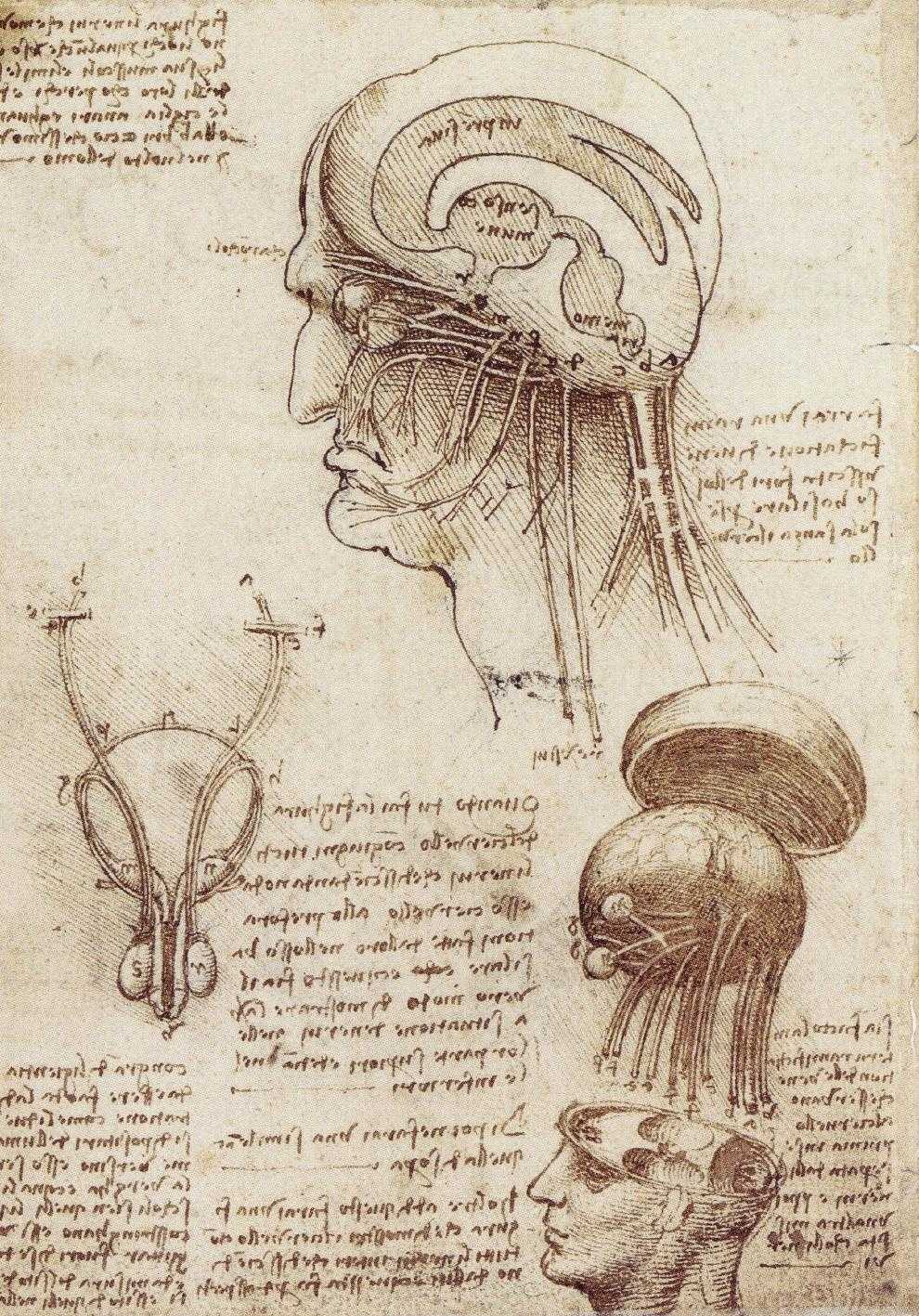

A drawing from Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbook of the brain and neuro system.

A drawing from Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbook of the brain and neuro system.

Ramachandran’s study even tried to define specific principles of art as they relate to Neuroscience. The idea behind this type of thinking almost says that if we correctly understand all the stimuli(color, shapes, etc.) accurately, we can create a particular and agreeable kind of art which will always invoke the proper emotional response. Artwork could be tested objectively, and it could be produced in a formulaic manner.

Another study “The Neural Correlates of Beauty” by Hideaki Kawabata and Semir Zeki presented several paintings to individuals who were asked to rate them as “beautiful,” “neutral,” or “ugly.” The participants viewed these same paintings again while their brain activity was being scanned with an MRI machine. The findings were in line with the principles defined by Ramachandran, as certain visual features in the paintings activated different parts of the visual cortex specific to the features in the paintings. The paintings which were identified as “beautiful” created the most activity in the emotional centers of the brain, while the paintings identified as “ugly” created the most activity in the motor cortex – an area of the brain associated with other aversive stimuli.

These neurological studies show us that the brain and the body play a part in determining, or at least interpreting what makes something beautiful. They also provide glimpses into the types of things we may learn about art in the near future. They do not, however, provide much insight at all as to why one thing is considered beautiful and another ugly. We can speculate, and perhaps draw some logical conclusions about the neurological effect of many different types of stimuli, but it is improbable that any amount of study could ever provide a formula for creating beauty.

It may be true that when we attempt to create something beautiful, we are trying to develop an appropriate and “agreeable” chemical response in a viewers brain. While scientifically accurate, this scientific way of thinking about the aesthetic experience and the arts does very little to inspire the artist and potentially limits the power of the arts.

The physiological response to beauty is an important factor in determining what is beautiful, but it also seems to be quite limiting. There’s too much that we don’t know about what is going on inside of our heads to entirely defer to science as able to provide us with all the answers.

Beauty and Philosophy

While the scientific studies on beauty are relatively recent, the study of beauty in philosophy has been a topic on the philosopher’s mind for thousands of years. In the philosophical study of beauty, we are allowed to discuss beauty as it relates to things that we may never understand through means of scientific research alone. We can introduce spirituality, thought, art and aesthetics without the need to prove our ideas outright.

Spirituality, perhaps, is a word even more difficult to define than beauty. It potentially carries with it the highly controversial connotations of religion, as well as a pre-requisite for some amount of willingness to believe in things not seen and ultimately not provable within the realm of science.

These matters were perhaps more easily discussed historically when the two disciplines—science and spirituality—were examined together. Plotinus, the Neo-Platonic philosopher of the middle ages, who inspired many of the humanists and much of Christian philosophy during the Renaissance, spoke of beauty in Ennead 1.6:

Let us, then, go back to the source, and indicate at once the Principle that bestows beauty on material things. Undoubtedly this Principle exists; it is something that is perceived at first glance, something which the soul names as from an ancient knowledge and, recognizing, welcomes it, enters into unison with it.

But let the soul fall in with the Ugly, and at once it shrinks within itself, denies the thing, turns away from it, not accordant, resenting it.

Our interpretation is that the soul—by the very truth of its nature, by its affiliation to the noblest Existents in the hierarchy of Being—when it sees anything of that kin, or any trace of that kinship, thrills with an immediate delight, takes its own to itself, and thus stirs anew to the sense of its nature and of all its affinity.

But, is there any such likeness between the loveliness of this world and the splendors in the Supreme? Such a representation in the particulars would make the two orders alike: but what is there in common between beauty here and beauty There?

Here Plotinus defines beauty as something which is perceived and recognized by the soul. His description is not entirely different from the scientific description offered in the two studies presented earlier. The main difference deals with understanding what it is that the mind recognizes in what it has perceived. Plotinus defines beauty as a connector of the physical world to that of the spiritual. The eye sees, the brain processes, and the soul (or spirit) is awakened to some degree because it recognizes something of the divine in the object which is seen. He goes on to say:

“This, then, is how the material thing becomes beautiful- by communicating in the thought that flows from the Divine.”

This idea that art can awaken some form of spiritual thought through the perception of beauty is at the heart of the concept of a “Spiritual Beauty.”

The French mathematician, Jules Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) stated:

The scientist does not study nature because it is useful; he studies it because he delights in it, and he delights in it because it is beautiful.

If nature were not beautiful, it would not be worth knowing, and if nature were not worth knowing, life would not be worth living. Of course I do not here speak of that beauty that strikes the senses, the beauty of quality and appearances; not that I undervalue such beauty, far from it, but it has nothing to do with science; I mean that more profound beauty which comes from the harmonious order of the parts, and which a pure intelligence can grasp.

This quote by Poincaré identifies an essential point in understanding this concept when he says: “…it has nothing to do with science…”, he speaks of a more profound beauty which can only be grasped by “pure intelligence.”

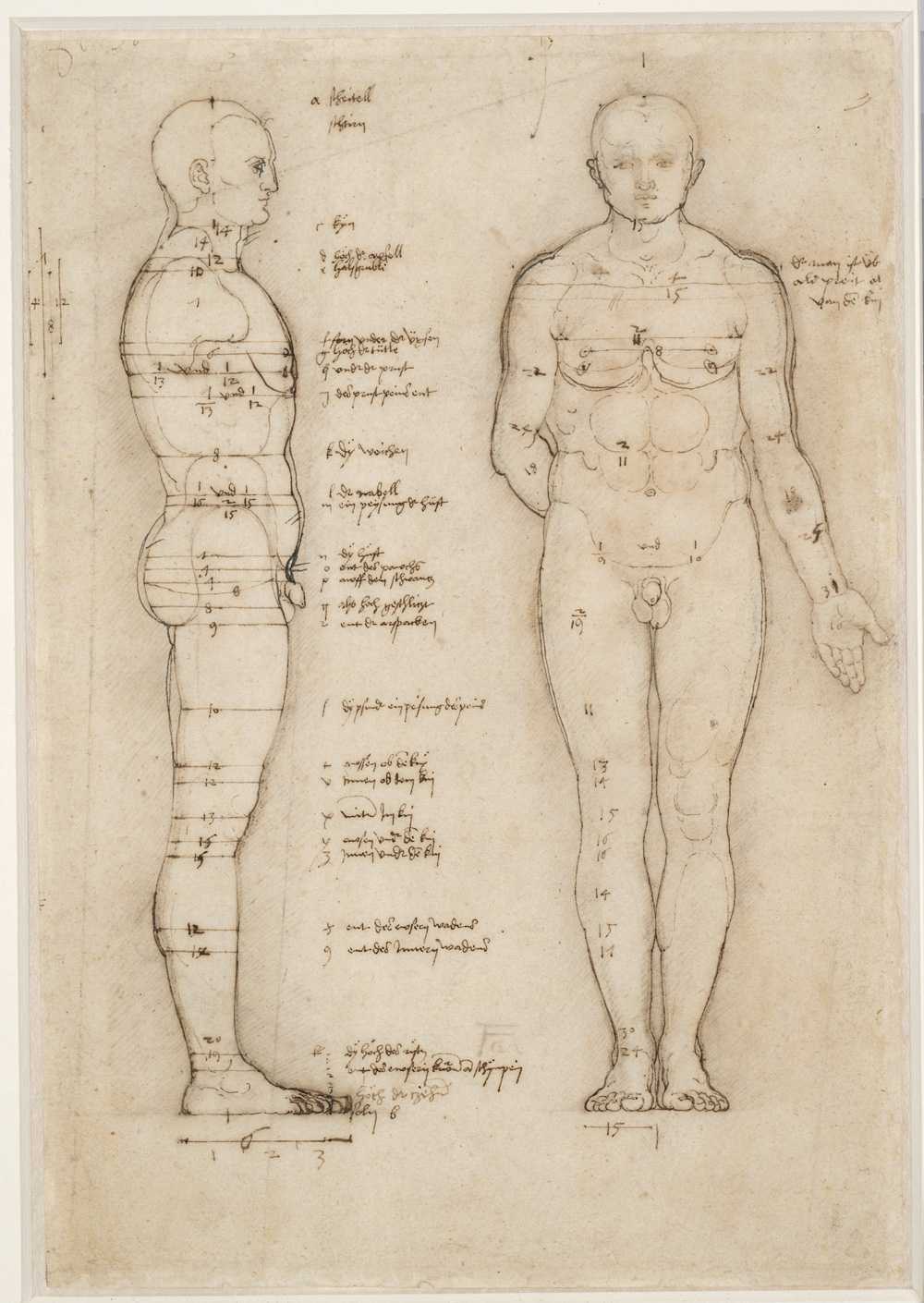

Albrecht Dürer and many other artists of the Renaissance believed that the key to beauty could be found in the harmonious proportions of the human figure.

Albrecht Dürer and many other artists of the Renaissance believed that the key to beauty could be found in the harmonious proportions of the human figure.

If it has nothing to do with science, beauty becomes very difficult to talk about, discuss, and ultimately impossible to prove with any of the tools that we have to do so. On the other hand, I don’t know anyone who hasn’t at some point in their life marveled at the beauty of a sunset, a landscape, the power of the ocean or the majesty of the stars and heavens.

This sense of beauty—which we all possess—is something that defies description, yet we are able to experience it, discuss it, and share our thoughts about beauty with others very quickly.

Beauty as a Spiritual Experience

The concept of beauty as a spiritual experience closely relates to Plotinus’ philosophy of beauty— the idea that art can help the mind draw connections to the spiritual aspects of life and nature. If an individual can look upon artwork and relate to it in some way that makes them experience happiness, be reminded of something positive, or recall an event or positive emotions from past experience, they have experienced a spiritual form of beauty.

The Shaker movement of the early 1800’s produced some of the best American design. Their concept of beauty rings true with this idea of a spiritual beauty—a beauty deeper than the surface appearance. In the book “Shaker Built” by Paul Rocheleau and June Sprigg this idea of beauty is expressed as follows:

“The appearance of things—including buildings—mattered in the Shaker world, but not in the same way that it generally mattered in the World…Physical homeliness was perhaps less of a handicap in the Shaker world than anywhere else because the beauty of the spirit was what was deemed important.”

In the Shaker world, the appearance of a thing or person mattered only to the extent that it revealed the underlying function. Whatever did not interfere with function, served the function.

S.N. Nasr in an essay titled “The Interior Life in Islam” discusses the role of beauty as a requirement for spirituality, and a necessary element for survival.

An understanding of the interior life in Islam would be incomplete without reference to the imprint of the Divine Beauty upon both art and nature. Islamic art, although dealing with a world of forms, is, like all genuine sacred art, a gate towards the inner life. Islam is based primarily on intelligence and considers beauty as the necessary complement of any authentic manifestation of the Truth. In fact, beauty is the inward dimension of goodness and leads to that Reality which is the origin of both beauty and goodness. It is not accidental that in Arabic moral goodness or virtue and beauty are both called Husn. Islamic art, far from being an incidental aspect of Islam and its spiritual life, is essential to all authentic expressions of Islamic spirituality and the gate towards the inner world.

From the chanting of the Holy Quran, which is the most central expression of the Islamic revelation and sacred art par excellence, to calligraphy and architecture which are the “embodiments” in the worlds of form and space of the Divine Word, the sacred art of Islam has always played and continues to play a fundamental role in the interiorization of man’s life.

Nasr puts art and beauty as being “central” and “fundamental” to spirituality. There may be one type of beauty which is purely scientific and instinctual, and there may be another which breaks the boundaries of scientific description and can only be fully appreciated and understood when it is looked at holistically and takes into account the spiritual and metaphysical aspects of humanity.

Gordon B. Hinckley—former spiritual leader of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—spoke of beauty in the following manner:

“…I believe in the beauty of nature, and I see and believe in the beauty of animals. I see and admire beauty in people. I am not so concerned with the look that comes of lotions and creams, of pastes and packs as seen in slick-paper magazines and on television. I am not concerned whether the skin be fair or dark. I have seen beautiful people in all of the scores of nations through which I have walked. Little children are beautiful everywhere. And so are the aged, whose wrinkled hands and faces speak of struggle and survival…”

His statement addresses an aspect of spiritual beauty, that of being able to look past superficial qualities toward an inner beauty, finding conditions in the “wrinkled hands and faces” that communicate to us in ways more profound than our visual perceptions.

Portrait of an Elderly Woman by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669).

Rembrandt believed that the faces of the elderly told the most exciting stories of life. His drawings reveal the poetry and beauty of old age.

Portrait of an Elderly Woman by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669).

Rembrandt believed that the faces of the elderly told the most exciting stories of life. His drawings reveal the poetry and beauty of old age.

Toward a Holistic View of Beauty

It does not make sense to separate the two views of aesthetic experience. It is a fact that our bodies produce chemical reactions to stimuli. It is also a fact that we don’t know everything about how the brain processes information. We will continue to learn more and more, but we will never understand everything.

The concept of beauty as a spiritual experience is not incompatible with the scientific view. The experience of spiritual beauty comes when the physical reaction to stimuli, triggers a spiritual experience when a connection made between something tangible (the artwork) to a positive thought not necessarily about the work itself. If a work of art could make someone think about the best moments of their childhood, ponder the love between a mother and her child, or reflect upon the mysteries of the universe in an uplifting way, the experience is spiritual in nature. Things that are beautiful for the qualities of their exterior trigger these same responses.

Can a beautifully crafted object trigger a spiritual experience in the viewer? I believe that it can. The human mind is perceptive, it can perceive the work by human hands. Not everyone experiences everything in precisely the same way. Our experiences are influenced by our past experiences, our knowledge, and our current state of mind. A spiritual experience is one that is drawn from our collective experience as members of the human family.

To take advantage of this holistic view of beauty, to engage your audience neurologically and spiritually, your work of art or design must communicate to all the senses. All the components of the work—the illustration, typography, design, and content—must work together to speak not only to the mind but to the soul. When every aspect of a work of art begins to align and condition the viewer towards this holistic experience, the possibility of making a spiritual connection improves.

Make your work more beautiful by considering all three aspects of beauty. Make your work trigger a beautiful neurological response. Make your work attractive to the philosophical thinker by implementing classical forms and aesthetics. Make your work beautiful by allowing the divinity and nobility of the human soul to show through.

When a viewer recognizes that element of beauty that you have infused into your art, it will give them satisfaction. It will provide them with joy. It will positively enrich their life, even if just for a moment.

If the end result of our work can create that spark which triggers a positive experience—touching both the mind and the soul—is there any reason to not make it beautiful?

References

- Conway, William Martin (translator), The Writings of Albrecht Dürer – New York: Philosophical Library, 1958

- V.S. Ramachandran and William Hirstein, “The Science of Art: A Neurological Theory of Aesthetic Experience.” Journal of Consciousness Studies, 6, No. 6-7, 1999, pp. 15–51

- Kawbata, Hideaki and Semir Zeki, “Neural Correlates of Beauty. J. Neurophsiol 91: 1699-1705, 2004

- Plotinus, translated by Stephen MacKenn. “[Ennead 1.6, On Beauty] (http://eawc.evansville.edu/anthology/beauty.htm){.link}” “Nature (philosophy).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. 8 Oct 2007, 00:38 UTC. Wikimedia Foundation, Inc. 19 Oct 2007.

- Hinckley, Gordon B. “I Believe,” New Era Magazine. Sept 1996.

- “The Interior Life In Islam.” Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. 17 Oct 2007

- Rocheleau, Paul, and June Sprigg. Shaker Built: The Form and Function of Shaker Architecture. New York: Monacelli, 1994.

- Poincaré, Henri. Science and Method. Transl Francis Maitland… New York: Nelson 1930., 1930.