Anyone who has ever presented their design work to any kind of group will have experienced—and will likely cringe—at the following scenario:

You’ve worked for weeks on solving a difficult design problem. You’ve gone through all the rigor of your design process. You’ve studied user behavior, you’ve dug through analytics to ensure that you’ve solved the problem. You’ve made a hundred sketches. You’ve made prototypes and have tested them in the wild. You’ve had heated debates with your colleagues and stakeholders made every acceptable compromise to meet needs and still deliver an excellent solution to the customer. Your solution works, it’s not perfect, but you’re confident it will solve the problem at hand and are prepared for the presentation.

Before you can even give justice to all your works, the highest paid person in the room—even the CEO—questions your specific choice in a particular shade of blue, and the spacing between secondary objects.

At this point, all is lost.

You didn’t really concern yourself with that particular blue, because it didn’t matter that much. You try to recover by suggesting that the color isn’t that important, and it can be easily changed, which only makes the problem more significant. Now the CEO questions all your decisions—

“If these designers can’t even choose the right blue, how can they be right about any of this?”

This scenario is dreaded by creative employees - but also despised by business leaders who are trying to make the most of a meeting. Nobody wants to talk about the things that don’t matter–the problem is that those things are often the most visible and most accessible to have an opinion about.

We often marvel at the pyramids of ancient Egypt, and might even wonder how they got that very last large rock to the very point of the pyramid when we still know that the thousands of blocks at the foundation were the most critical pieces. The Great Pyramids of Egypt still stand, and are still great, even though the apex and surface treatment is no longer intact.

We often marvel at the pyramids of ancient Egypt, and might even wonder how they got that very last large rock to the very point of the pyramid when we still know that the thousands of blocks at the foundation were the most critical pieces. The Great Pyramids of Egypt still stand, and are still great, even though the apex and surface treatment is no longer intact.

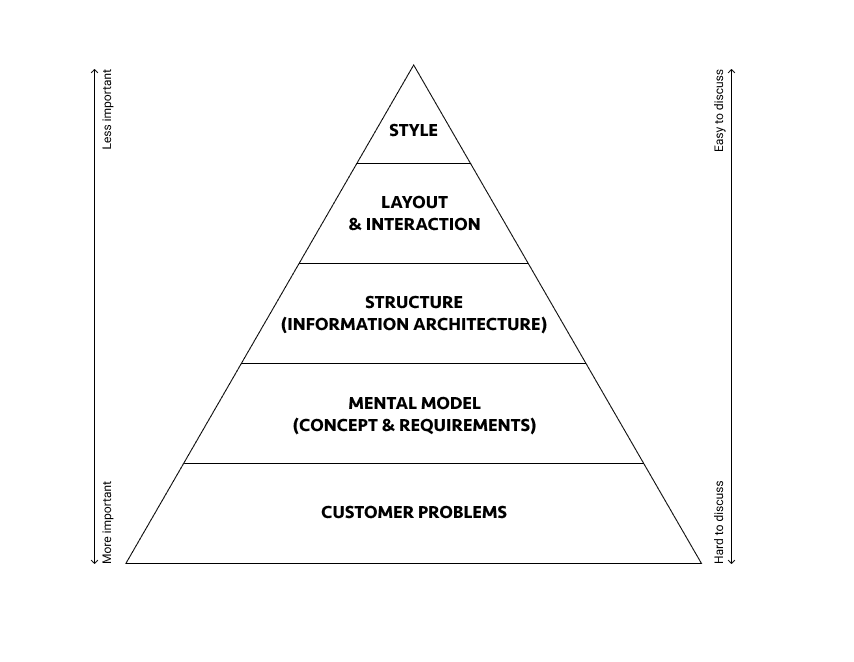

Penrod’s Pyramid

A design project or any sizable complex project has many aspects that contribute to its final form. At the base of the pyramid is the fundamental problem we’re trying to solve - everything is built upon this.

The next layer is the mental model - how the problem is perceived, how it affects an individual, and how a solution fits into their view of reality.

The next layer is the arrangement of the information in the person’s world. How they access the solution and how the new solution fits into the bigger picture. This includes some graphical treatments such as layout, copy choices, and flow.

The final layer is the visual appearance and style—a vital layer—no pyramid is complete without completing the apex. However, it is most likely the least important aspect of the whole thing. If proper attention has been paid to the lower layers, the problem will be addressed, and the person will be able to use the proposed solution.

Hard Things are Hard

It’s our natural tendency to avoid them and focus on the things that are easier. People think that they are obligated to have an opinion. The higher your rank and title, the more pressure you have on you to give some feedback. If you don’t love what you see right off, and you don’t understand it all - it’s much easier to start to talk about things you might not like, than it is to wait for a full explanation to understand everything else.

It can be especially challenging when those in the meeting don’t have the same vocabulary, background or training in design. A person’s own discomfort and unfamiliarity with the presented material almost force them to talk about things that they can have an opinion on. It’s much easier to jump in and criticize an apparent detail or make personal comments than it is to try and understand what is typically a complex and probably messy problem.

References/Additional Information

- Penrod’s Law is named after Josh Penrod (CPO at Podium), who used this pyramid diagram to explain to people that they were talking about the wrong things.

- Harvard Business Review published this article on time lost in meetings talking about the wrong things.

- Meetings cost lots of money. If these meetings are spent talking about the wrong thing, we’re not only wasting time but seriously missing the valuable time that needs to be used to discuss the more important things.