Chinese workers employed by the Transcontinental Railroad in the early 1800’s brought with them an ointment made from the Chinese water snake. This ointment has been used for centuries in China, and in its original form was quite useful for the treatment of fever, headache, bursitis, and arthritis.

Inspired by tales of this miracle cure, Clark Stanley an entrepreneurial cowboy in the west claimed to have studied with a Hopi medicine man in Arizona learned the secrets of snake oil. He worked with a Boston druggist and brought to market his “Snake Oil Liniment.”

The “Rattlesnake King” - Clark Stanley wrote about his life as a Cowboy in the American West. He duped thousands into buying his snake oil, which he claimed to be a miracle cure for common ailments.

The “Rattlesnake King” - Clark Stanley wrote about his life as a Cowboy in the American West. He duped thousands into buying his snake oil, which he claimed to be a miracle cure for common ailments.

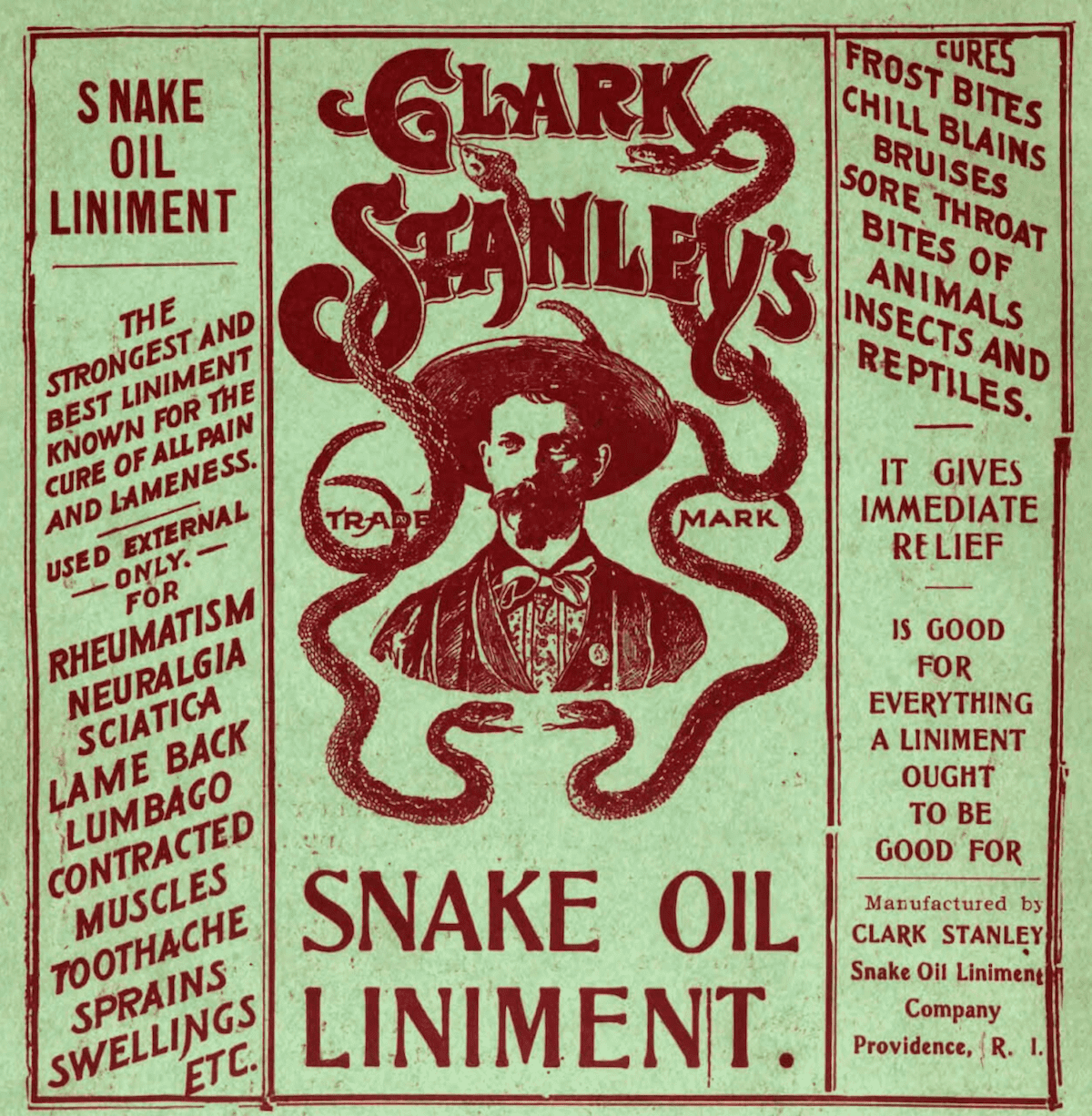

He claimed that his version had harnessed the oil from western rattlesnakes and was a miracle cure for everything. The label included the following claims:

- The strongest and best liniment known for the cure of all pain and lameness.

- Used externally for rheumatism, neuralgia, sciatica, lame back, lumbago, contracted muscles, toothache, sprains, swellings, etc.

- Cures frost bites, chill blains, bruises, sore throat, bites of animals insects and reptiles.

- It gives immediate relief, is good for everything a liniment ought to be good for.

A label from Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment promises to cure anything that might need curing.

A label from Clark Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment promises to cure anything that might need curing.

He began marketing his product at medicine shows and gained attention at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

His product took off and was peddled across the United States, drawing enough attention to warrant an investigation by the Bureau of Chemistry (forerunner to the FDA).

In 1916 a shipment of Stanley’s Snake Oil Liniment was seized by federal authorities. It was examined and found to be drastically overpriced and of limited value. It was also found to contain 0% snake oil - the advertised miracle ingredient.

Stanley faced federal prosecution for fraudulently peddling mineral oil and was fined $20 after a plea of no contest.

There is no evidence that Stanley’s liniment provided any of the benefits that it advertised. It is for this reason that “Snake Oil,” and “Snake Oil Salesmen” became synonymous to describe the charlatan - anyone who falsely advertises or intentionally deceives to make the sale.

Are designers peddlers of Snake Oil?

This story brings us to question we need to ask ourselves: Do the things we do make a difference? Or are we just peddlers of snake oil?

Design snake oil is anything that we’re selling as part of our services that doesn’t solve the problems we’re claiming it will solve.

I submit that there are many things that designers aim to sell that fall into this category. Many of these “design ingredients” are useful in specific practical applications, but not always for the problems we claim they will solve.

Here are a few examples of the snake oils we’re selling:

Design Process Snake Oil

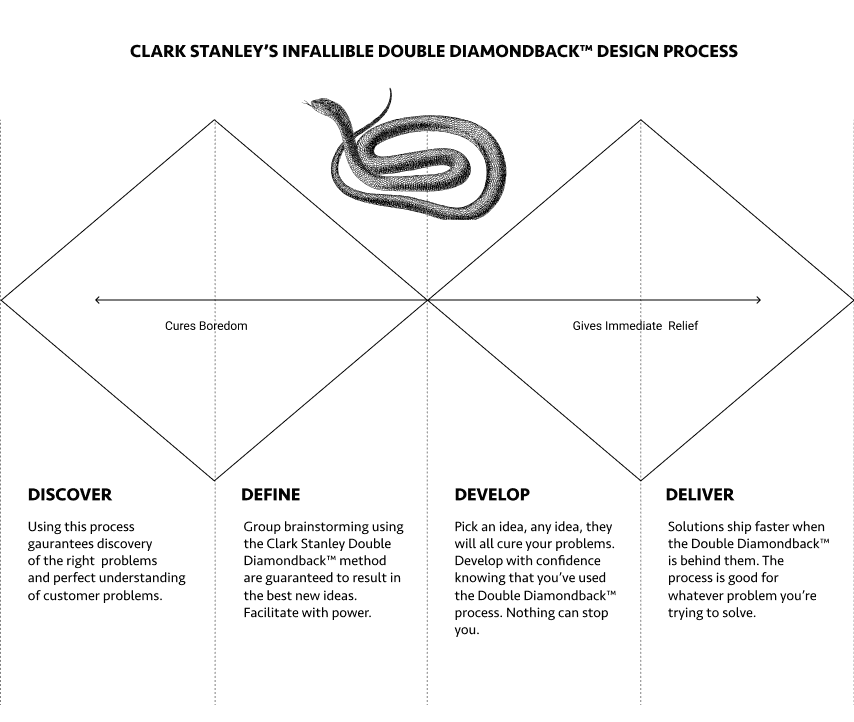

“Process” is one of the most common forms of design snake oil - the very idea that there’s a step-by-step way to solve every design problem.

You may prefer working a certain way, and there are probably benefits in certain situations to doing it your way.

It’s also possible that another process or no process at all may turn a better result.

I remember working extensively on developing a process that I thought would position our UX team better, and yield better results. I developed it during a successful project and thought I had come across an exact process for design. The next project where I tried to follow this same process, It not successful

If you’re selling a process or method and claiming that it will solve any business or design problem, you’re selling snake oil.

When is process not snake oil? Your design process is valuable part of the work that you provide. It helps focus the work, gives clear objectives, and helps guide any project to some conclusion. You can sell your process as a guide, you can even sell it as something that will improve the likely hood of success - but if you believe your process is an infallible route to the best solution, you’ve just packaged it as Snake Oil.

”Look and Feel” Snake Oil

It’s easy for trained visual designers to focus and potentially over-index their efforts on visual design as a primary solution.

Visual design can always be better and more unique. It can also be better and more visually stunning and still not solve any problems.

Stanley’s Snake Oil contained an ingredient similar to camphor that made the skin tingle and smelled like it was doing something. Loving the way it feels or smells does not mean that it’s doing anything for you.

There’s no reason not to make everything beautiful. We need to be careful that we don’t let the beauty of something sell ourselves (and our users) a product that doesn’t do what it needs to do.

Do our designs solve real problems for our users, or do they solve problems for us? For our portfolio? For our trained eyeballs?

Like the visual design, too much focus on a particular font, web font, or style of typography can create distractions for both designers and users that emphasize the wrong problems.

Legibility, readability, and accessibility are real issues, and typography can help all of those things, and it can hurt all of those things too.

It’s important to remember that the base elements of design, while very important to designers (and it should be essential) they are probably not even remotely the most important thing for the customer.

System fonts may very well solve all of your real typography problems, and your customers will appreciate faster loading times way more than they care about your favorite Type Designer.

If you are selling a “redesign” or an update to the “look and feel,” claiming that it will be the solution to a problem that it won’t solve, you’re selling snake oil.

If you’re selling an update to the typography as the solution to a problem that typography doesn’t solve, you’re selling snake oil.

When is the look and feel not snake oil? Visual design solves real problems including hierarchy, communication, legibility, and helps with comprehension. Aesthetics in general, are a key part of any design project. As a designer, it’s your job to make the things you make look nice. The client you have may need a stylistic makeover to attract or generate trust with a particular audience. Visual style won’t solve hard interaction problems, but it might help get more eyeballs on your banner ads.

Technological Snake Oil

Technology is amazing. However, in and of itself, it is not a cure for any real problems.

Sometimes, technologies that are great for developers, or designers are terrible for customers. We are quickly caught up in the spell of technology and it’s easy for us to believe that the latest technology trend, animation technique, or specific design tool feature, will magically solve customer problems.

AR, VR, Voice, Apple Watch, 3D, Gamification, immersive & rich experiences, etc. The list goes on - will these technologies really solve the problems you are trying to solve? Or, will they just be fun to work on?

Do the technologies solve problems for our customers, or do they only make it more interesting for us?

If you’re selling the use of new technology as a solution for something that technology won’t solve, you’re selling snake oil.

When is design technology not snake oil? When a technology directly impacts the problem you are working on, it isn’t snake oil. This is when things become the most amazing and fun to work on.

Personal Bias Snake Oils

Whether you like something or not is irrelevant. It is also not a reason to sell an idea or design that doesn’t work.

There are indeed times when something that you like matches precisely the preferences of your customers and solves a real problem for them too.

Unfortunately, this is not always the case, and in my experience seems to be more of an exception than the rule.

“I like it” is the definition of bias - and you have to double check it.

We’re sometimes fortunate to develop solutions that we love, that also work for our customers. And there’s no reason ever to give up trying to do that.

Our own biases can be so powerful that we have to work extra hard to keep them out. We should continuously verify our work with real customers and do whatever we can to avoid the pitfalls of confirmation bias in our testing and validation.

If you’re selling something because you like the way it smells, the way it looks, or because it fits within your personal biases and not because it solves real problems for real customers, you’re selling snake oil.